Introduction

If farmers’ first lines of defense against climate hazards are insufficient or not accessible, then a “last resort” for adaptation could be to switch to an alternative crop. This represents a move from additive or synergistic incremental changes to more transformational change.

Image credit: ©2016CIAT/GeorginaSmith

Asking a farmer to change crops, is likely to be more difficult to implement than incremental change

We deliberately use the phrase “last resort” because transformational change, such as asking a farmer to change crops, is likely to be more difficult to implement than incremental change. Switching to a new crop brings risk and demands increased knowledge compared to working with familiar crops. The resistance to adoption of new crops is, therefore, likely to be higher than changing the way existing crops are grown. New crops may also require supply chains and markets to be developed if that commodity is not already grown in an area.

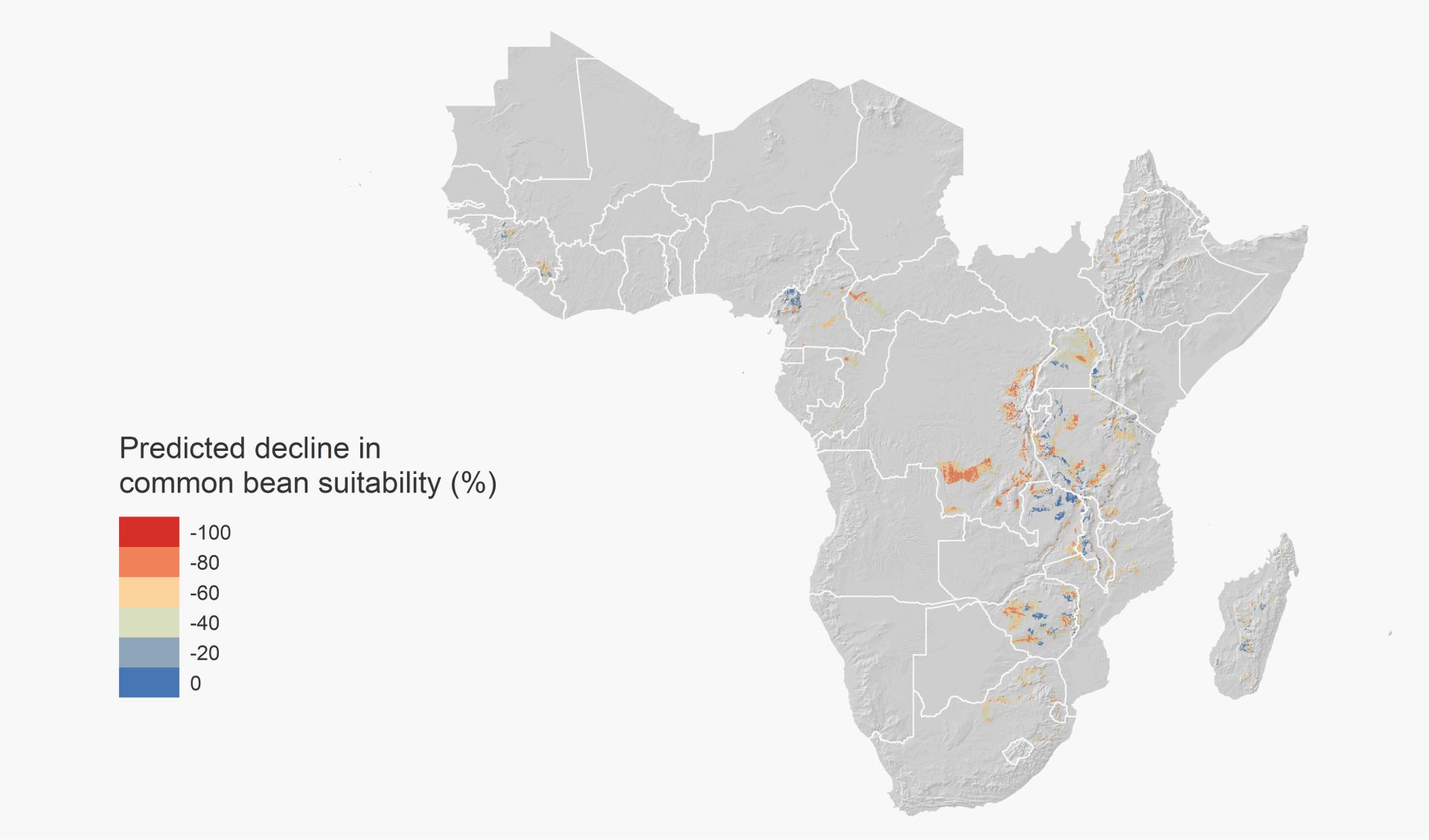

Nevertheless, common bean is a valuable and nutritionally important crop that is highly sensitive to climate change. Unless drastic measures are taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, there may be areas where the crop becomes unviable despite our best adaptation efforts.

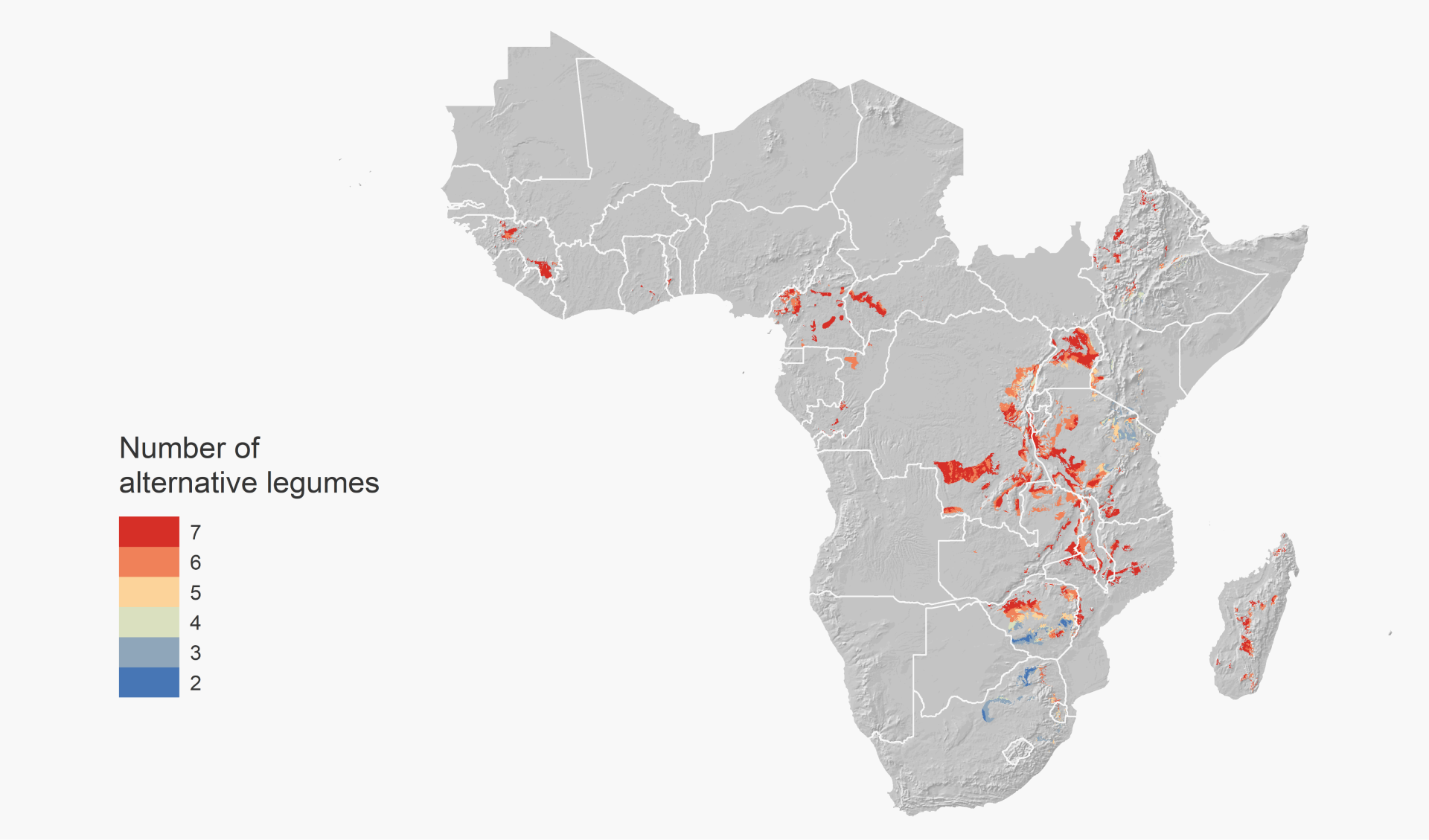

Map 1 Number of alternative legumes

There are alternatives, although the number of suitable species varies

The most severe declines in total bean suitability area are seen in Uganda (27.3%), Zimbabwe (26.4%), Tanzania (20.1%) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (15.7%). Fortunately, of the seven other legumes modeled, there are alternatives, although the number of suitable species varies. Uganda and DRC typically have six or seven alternatives to choose from, but southwest Zimbabwe and South Africa only have two or three.*

Legumes with higher heat tolerance and lower rainfall needs, such as pigeonpea and cowpea, appear to be almost universal substitutes in the zone of common bean decline, whereas soybean and groundnut appear to be the least suitable alternatives. We can zoom into nations and smaller areas to see which legumes work in specific contexts. In South Africa, only cowpea, lentil and pigeonpea are viable alternatives whilst, in Uganda, these species are joined by chickpea, broad bean, groundnut and soybean.

Map 2 Predicted decline in common bean suitability

There are many factors other than climate that need to be considered when evaluating the suitability of alternative crops

Where farming system transformation is needed, there are many factors other than climate that need to be considered when evaluating the suitability of alternative crops. Commercial farmers will evaluate a crop based on its profitability (e.g., yield, market price, access and volatility), practicality (e.g., access to competitive varieties and compatibility with farm infrastructure) and reliability (vulnerability of the crop to pests, diseases and climate hazards). For smallholder farmers, nutritional and cultural factors will also be important considerations, especially if the focal crop is a significant part of their household diet. If an alternative crop yields fewer calories and/or macronutrients per unit area, does not taste as good or requires more effort to prepare or process, then its value as a substitute crop will diminish.