Introduction

It is no coincidence that conflict and instability are a feature of daily life for millions of people subjected to increasingly frequent extreme events. There is a growing body of peer-reviewed literature that has successfully linked at least one climate-related variable (e.g., increased temperatures, changes in rainfall patterns, etc.) with various types of conflict (interpersonal, intergroup, or societal collapse).

Image credit: Patrick Sheperd

While climate change cannot be identified as the only driver, it may increase susceptibility to conflict

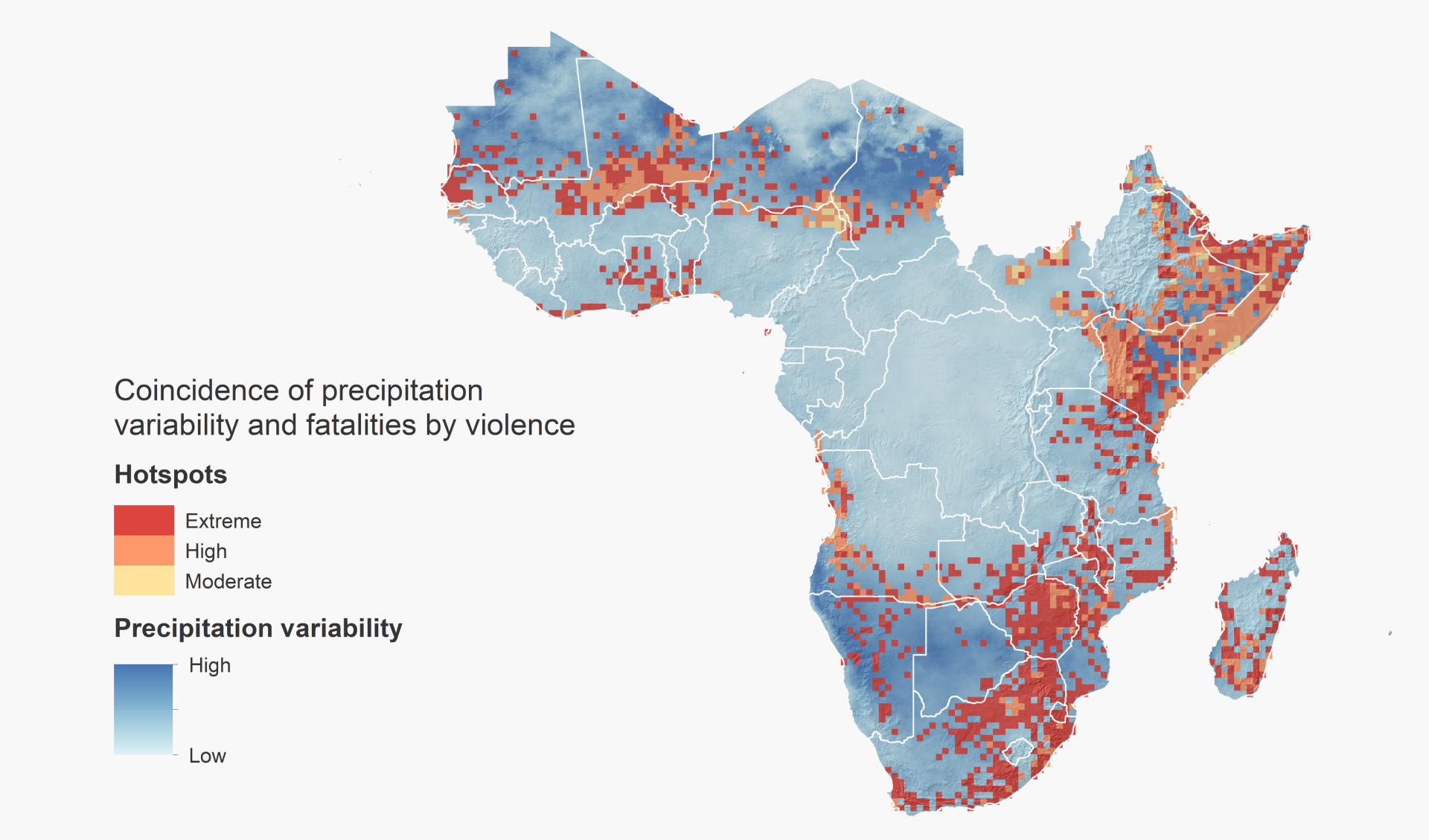

Map 1* shows that a total of 47,340 “conflict events” took place across sub-Saharan Africa between 1997–2019, which broadly reflect areas of high precipitation variability. These are primarily located along the Sahel, in North Africa, the Horn of Africa and Southern Africa. While climate change cannot be identified as the only driver, it may increase susceptibility to conflict by amplifying pre-existing inequalities and vulnerabilities. This is underpinned by environmental, economic, social and political influences.

Map 1 Coincidence of precipitation variability and fatalities by violence.

Rainfall variability and water scarcity are substantial threats

From an environmental standpoint, rainfall variability and water scarcity are substantial threats to those whose livelihoods require rainwater for consumption, livestock production and arable agriculture (Salehyan and Hendrix, 2012). This may lead to intercommunal conflict over access to wells and riverbeds (Kahl, 2006), whilst simultaneously forcing pastoralists to sell their livestock and thus become more susceptible to future climate shocks (Theisen, 2017).

Economic shocks in fragile countries can expose young, unemployed people to recruitment by armed groups

Economic growth in poor countries across SSA has been shown to drop by more than 2%, following a 1°C temperature rise. In addition to the indirect impact of reduced harvests on economic activity, this temperature increase may also result in lower labor productivity. In turn, this can lead to rising prices and a heightened risk of violent conflict (Dell et al., 2012). Moreover, economic shocks in fragile countries can expose young, unemployed people to recruitment by armed groups. These may include extremist groups like Al-Shabab in Somalia, which offers cash and other benefits to individuals trapped in poverty and lacking alternative sources of earning a livelihood (Maystadt and Ecker, 2014).

Forced sale of livestock due to a climate shock may reduce their mobility, and hence increase their vulnerability

Socially, the mobility changes which climate events demand of pastoralists in particular seem to increase their vulnerability to conflict. Forced sale of livestock due to a climate shock may reduce their mobility, and hence increase their vulnerability to insufficient future rainfall (Maystadt and Ecker, 2014). Alternatively, moving location due to the lack of food, fodder, water and other resources might lead to conflict with settled communities (Theisen, 2012).

Preventing pastoralists and semi-pastoralists from being drawn into civil conflict requires carefully targeted programs

Finally, and unsurprisingly, fragile and unstable political environments make overcoming such difficult situations especially challenging (Theisen, 2017).

In spite of these issues, potential solutions exist. As Map 1 shows, the Horn of Africa is stricken by frequent climate hazards (droughts, dry spells and floods), compounded by the fragility of the region’s natural resources. In this region, preventing pastoralists and semi-pastoralists from being drawn into civil conflict requires carefully targeted programs that provide opportunities to participate in credit systems that drive growth in the livestock sector, develop alternative income-earning opportunities, and establish social safety nets.

The interactions between climate and the political, social, economic and environmental drivers of conflict are complex

Furthermore, developing formal insurance mechanisms as well as investments in marketing and infrastructure in the livestock sector can help reduce the pressure to liquidate herds. This can also help prevent the collapse of livestock prices and rapid falls in household incomes that can push people into vulnerable situations, which can then lead to violence.

The interactions between climate and the political, social, economic and environmental drivers of conflict are complex and far from fully understood. Continued research and mitigating interventions will be required if further climate-related unrest is to be minimized.