Introduction

In addition to high temperatures, agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa is exposed to a plethora of other hazards. Around 95% of African food production is rainfed (You et al., 2011; Xie et al., 2018), which means that seasonal excess water and drought play a key role in determining crop productivity.

Image credit: @2011CIAT/NeilPalmer

Drought can typically affect between 20–30% of agricultural areas in sub-Saharan Africa

Rojas et al. (2011) estimated that in a given year drought can typically affect between 20–30% of agricultural areas in sub-Saharan Africa, and a single event can reduce production by up to 20% (Kim et al., 2019). Excess water can also hinder crop productivity through reduced root aeration and increases in root-related diseases (Olgun et al., 2008; Singh, 2015).

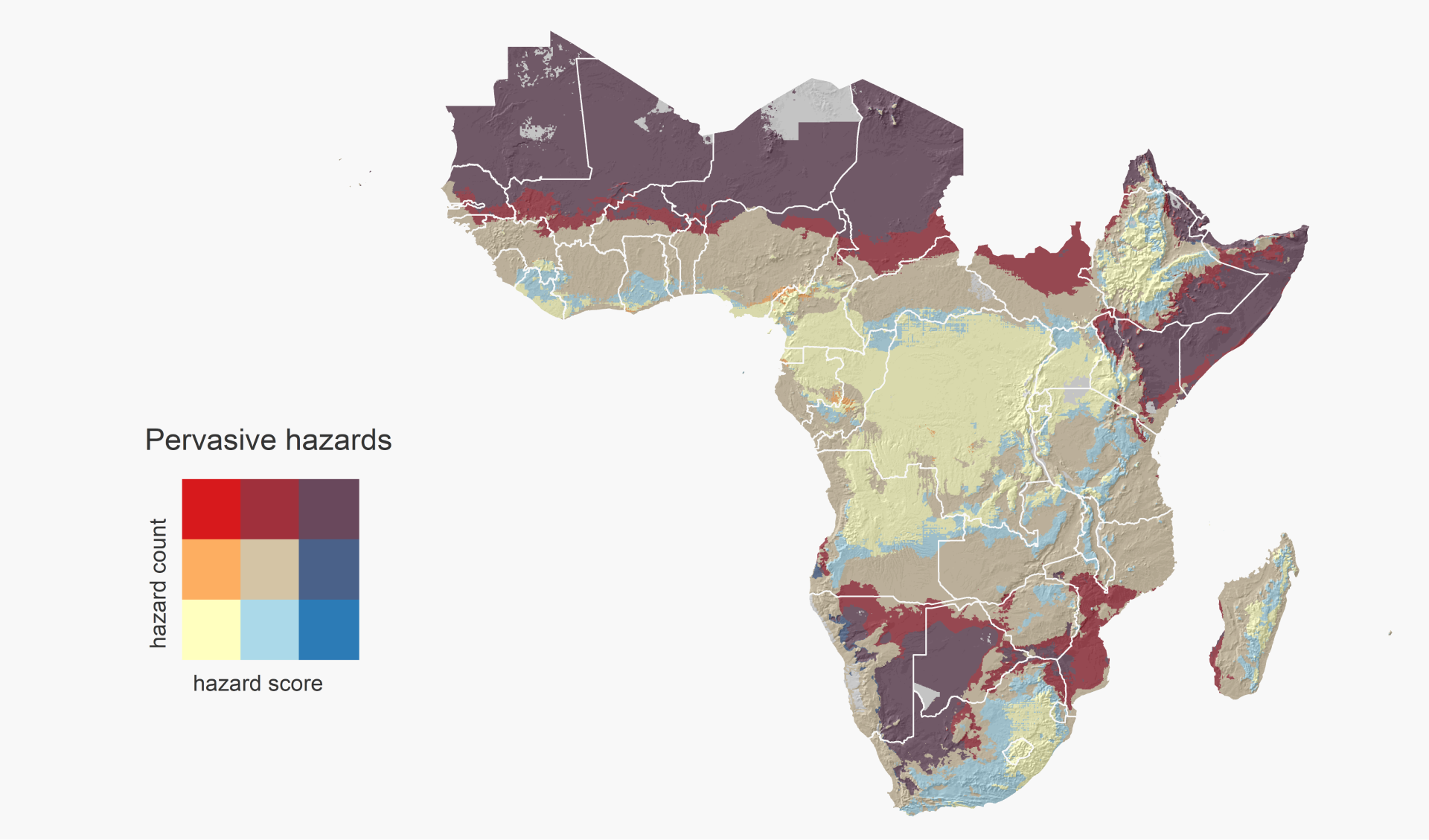

Map 1 Total hazard score (total sum of all reclassified hazards) overlaid with the number of hazards that are considered as being extreme or severe. Hazards included are drought, heat and precipitation extremes.

Stresses caused by heat, drought and waterlogging are complex

Stresses caused by heat, drought and waterlogging are complex because the intensity, timing and duration of these hazards can vary in space and time, sometimes within a relatively small geographic area, Sonwa et al (2017) analyze climate risk in nine countries in sub-Saharan Africa and identify a total of 17 specific hazards, all of which cause different types of disruption to agricultural production, including food insecurity and complete abandonment of agricultural activities.

The picture is bleak under present-day climate conditions

Map 1 overlays hazard datasets to identify geographies with the incidence of multiple hazards*. The picture is bleak under present-day climate conditions, and climate change is projected to both intensify local hazards and expand the amount of arable land subjected to multiple climate hazards.

The co-occurrence of multiple hazards makes these areas increasingly inhospitable

The co-occurrence of multiple hazards makes these areas increasingly inhospitable, and crop production and livestock keeping extremely difficult. As a result, areas have limited human populations and low livestock density, little to no cropland, and livelihoods consist mostly of small-scale subsistence farming.

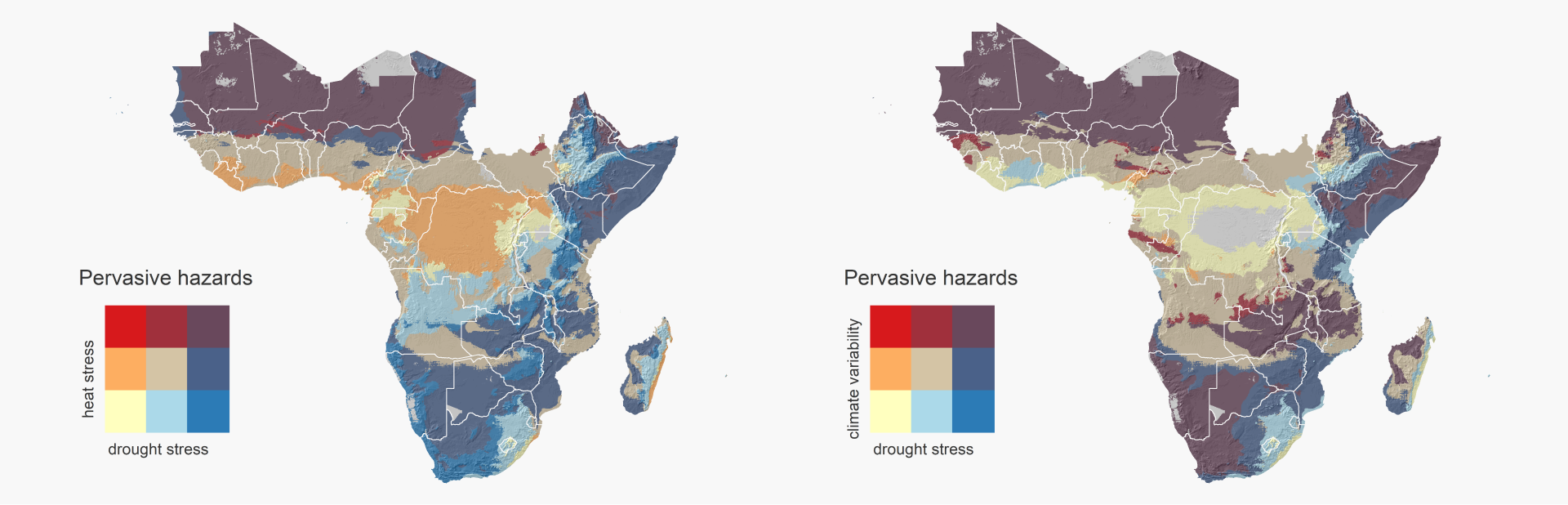

Map 2 (left) Heat stress and drought stress, Map 3 (right) Heat stress and climate variability

Farmers and livestock struggle to cope with hot conditions during the dry months

In the Sahel, where heat stress is greatest and co-occurs with drought (see Map 2), farmers and livestock struggle to cope with hot conditions during the dry months (especially around April–May). Crops are planted when the rains finally start, and temperatures decrease just enough to bearable levels for farmers to work the land (around late May).

In many of these areas, livelihoods are on the edge, and migration and conflict are also prevalent

However, many dry days at the start of the rainy period can lead to crop failure, leading to food insecurity for those unable to re-plant. During the growing season (June–September), intermittent drought can affect crops, whereas heat stress will typically strike at the end of the season, affecting both crops and farmers as they harvest. In many of these areas, livelihoods are on the edge, and migration and conflict are also prevalent.

Pasture availability can fluctuate substantially from year to year as a result of drought

A similar picture can be drawn for the Horn of Africa and Southern Africa, where heat stress is less problematic, but drought and climate variability and extremes pose major challenges (see Map 3). In these areas, pastoralism is the main livelihood type either by nomadic herders or partly settled livestock keepers. Pasture availability can fluctuate substantially from year to year as a result of drought.

In years of extreme drought and low pasture availability, pastoralist groups may experience food insecurity, compete with other nomadic groups and settled farmers for resources and land, or abandon their lands entirely.

As climate change intensifies, temperatures increase and rains become less predictable

Many other parts of sub-Saharan Africa experience multiple stresses. For example, most of East and Southern Africa, experience moderate levels of heat stress together with severe levels of drought (Map 2). Likewise, many parts of Eastern and Southern Africa experience either mild or severe climate variability and extremes jointly with drought (Map 3).

As climate change intensifies, temperatures increase and rains become less predictable, farmers will require adaptation options and adequate advice and training to be able to move toward a food-secure pathway.