Introduction

Africa is likely to experience drastic future climate hazards in relation to high temperatures during the growing season, reductions in the length of the growing season, increased climate variability, and greater incidence of floods and droughts.

Image credit: ©2012CIAT/NeilPalmer

The food sector is highly vulnerable to these climate hazards

In particular, reductions in the number of reliable crop-growing days per year, and increases in areas in which the average maximum daily temperature moves above 30°C consolidate as critical climate hazards for several major crops in the continent.

Given that smallholder farmers practicing rainfed and subsistence agriculture represent a high percentage of the population engaged in farming in Africa, the food sector is highly vulnerable to these climate hazards.

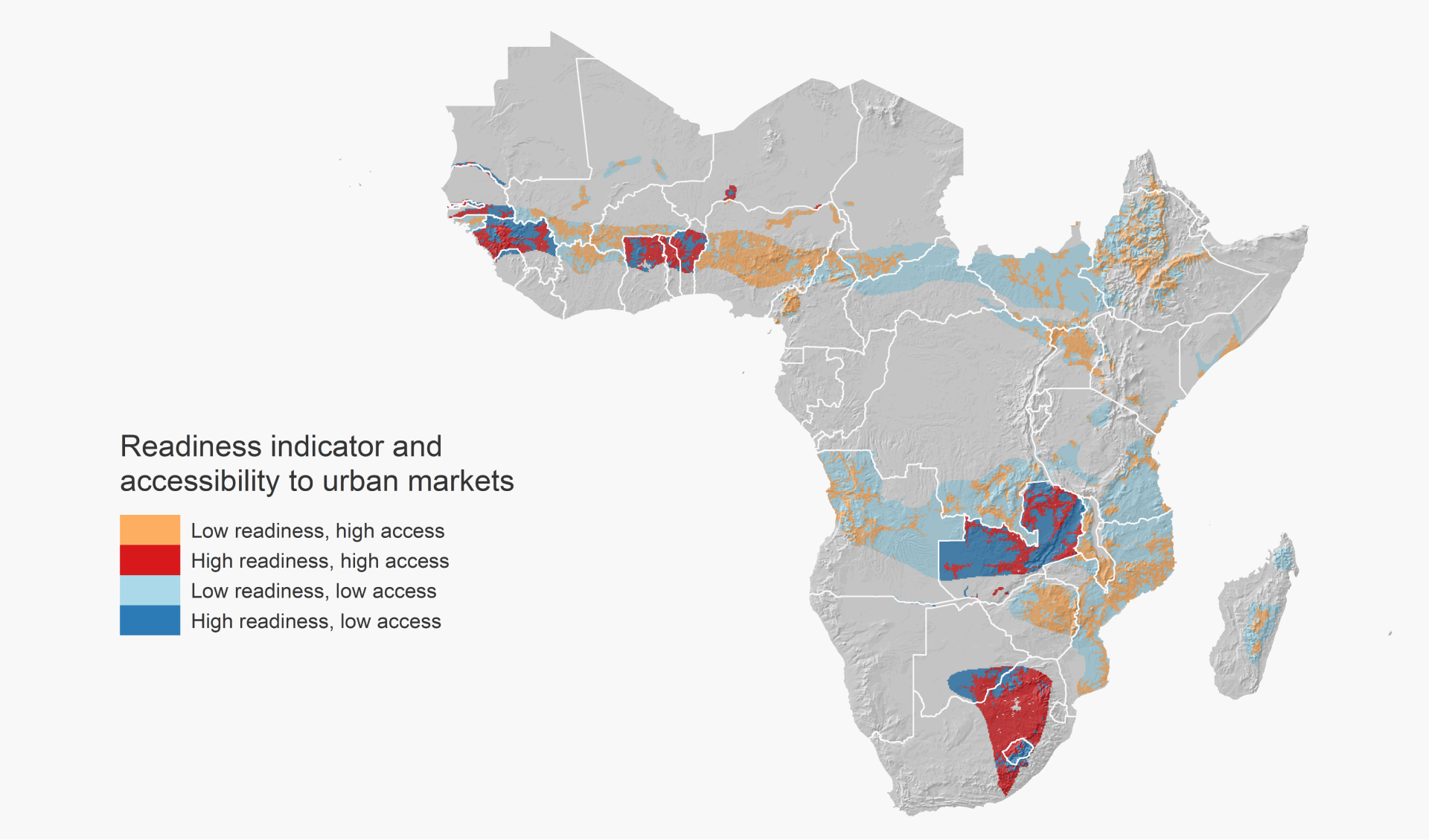

Map 1 “Adaptation domains” defined by the combination of future climate hazards and exposure, mapped for different adaptive capacities*.

Hazards become particularly dangerous in areas with socio-economic challenges

The hazards become particularly dangerous in areas with socio-economic challenges, such as a high prevalence of stunting in children under five years old, and where livelihoods depend on subsistence farming of cereals and roots, including maize-based mixed cropping systems.

Properly evaluating, supporting and scaling the most relevant and cost-effective of these options in local contexts remains challenging

While a variety of adaptation options are available to respond to climate change, properly evaluating, supporting and scaling the most relevant and cost-effective of these options in local contexts remains challenging. In particular, in order to promote innovation for adaptation options, countries will require:

- An appropriate business environment that facilitates investment from the private sector;

- Social stability and institutional arrangements that contribute to reducing investment risks;

- High capacity for good governance that reassures investors that invested capital could grow with the help of responsive public services and without significant interruption;

- Social conditions that help society make efficient and equitable use of investments, e.g. access to credit and infrastructure for the most vulnerable while ensuring training and information about new adaptation options;

- Accessible urban markets, which can unlock the potential for investments and business opportunities, and contribute to more resilient and productive farming systems.

Map 1 presents hotspots where this enabling environment is already high and capable of rapidly responding to adaptation options. In these areas, in specific pockets in Southern and humid West Africa, “high readiness” means that the farming population appears well positioned to make effective use of investments for adaptation thanks to a safe and efficient business environment and accessibility to urban markets. These areas constitute fertile ground for investments in adaptation options.

Many adaptation options are suitable in the areas shown in Map 1. These range from the adoption of crop varieties that can tolerate stresses, such as water submergence, drought, high temperature, and pests and diseases to fundamentally changing farming systems, such as shifting from crops to livestock, shifting to different livestock types, or shifting to different crops. But for adaptation to be effectively implemented, “high readiness” (red, dark blue areas) would be fundamental to ensuring that small-scale farmers rapidly adopt new technologies and practices. Where readiness is low (light orange and light blue areas), major investments are required to raise farmers’ adaptive capacity. In areas of high accessibility to urban markets, adaptation can quickly trigger positive shifts in farming systems as local economies can be highly responsive to consumer demand.